BEAUTY

Inside a New Monograph Celebrating the Legacy of Photographer David Armstrong

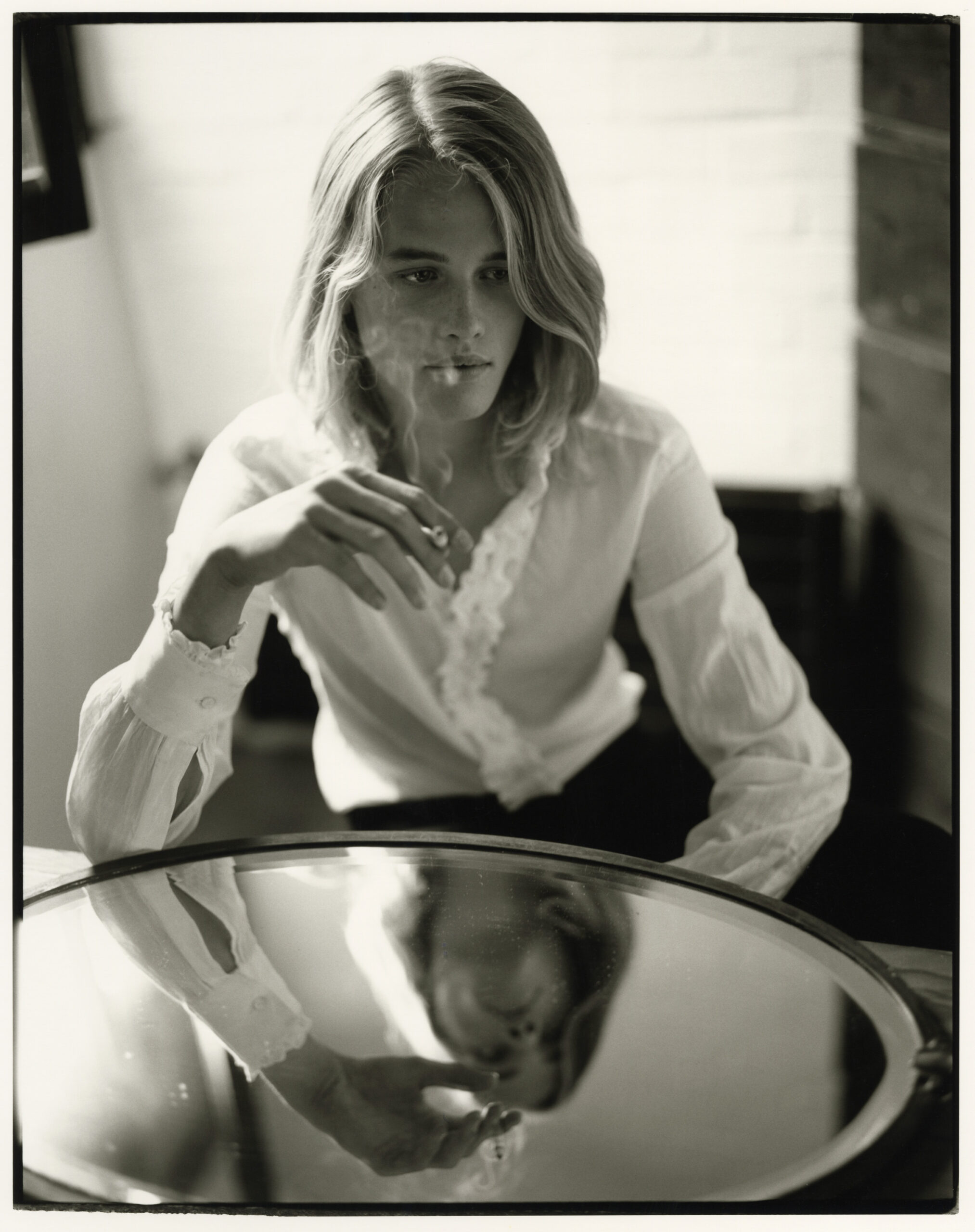

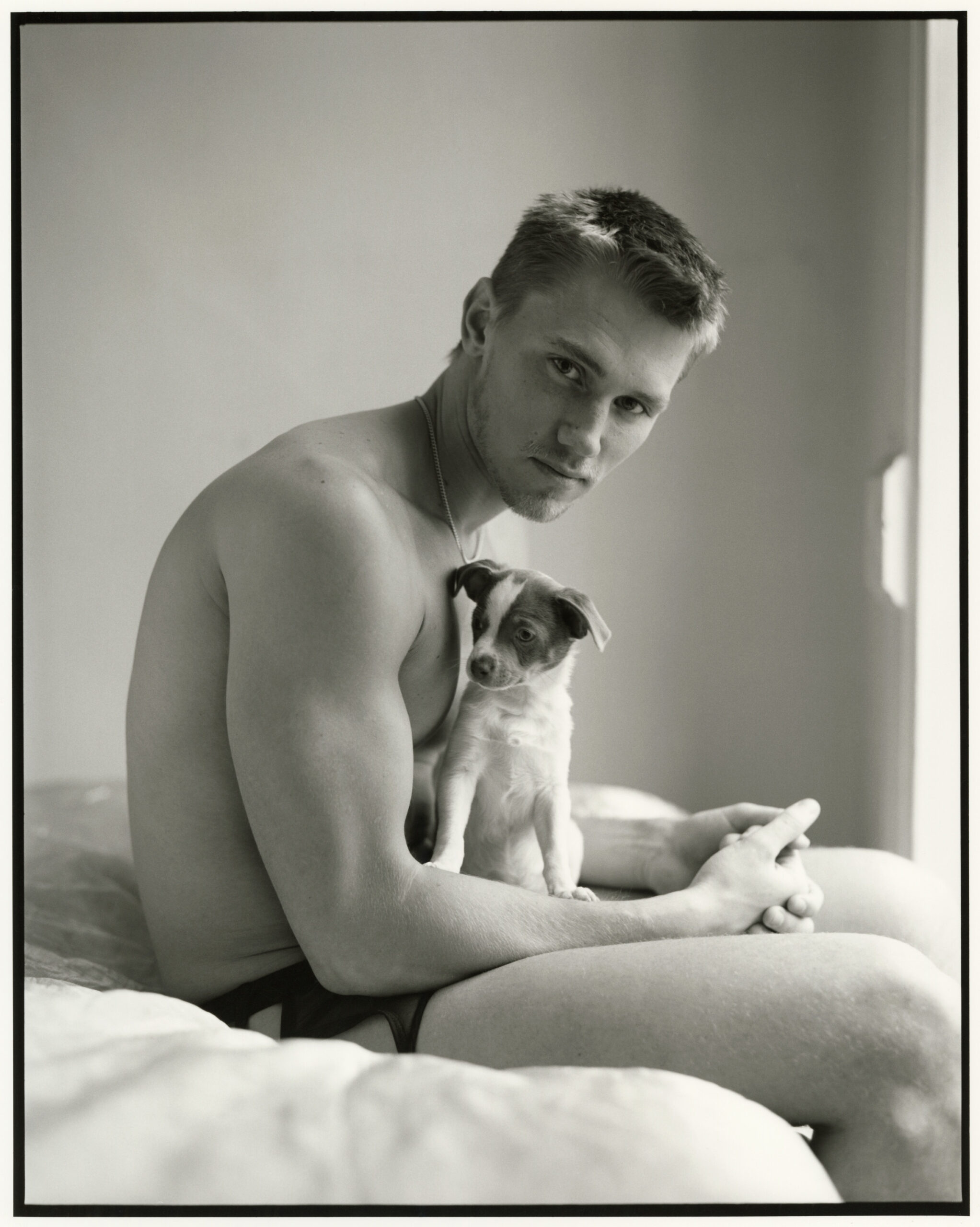

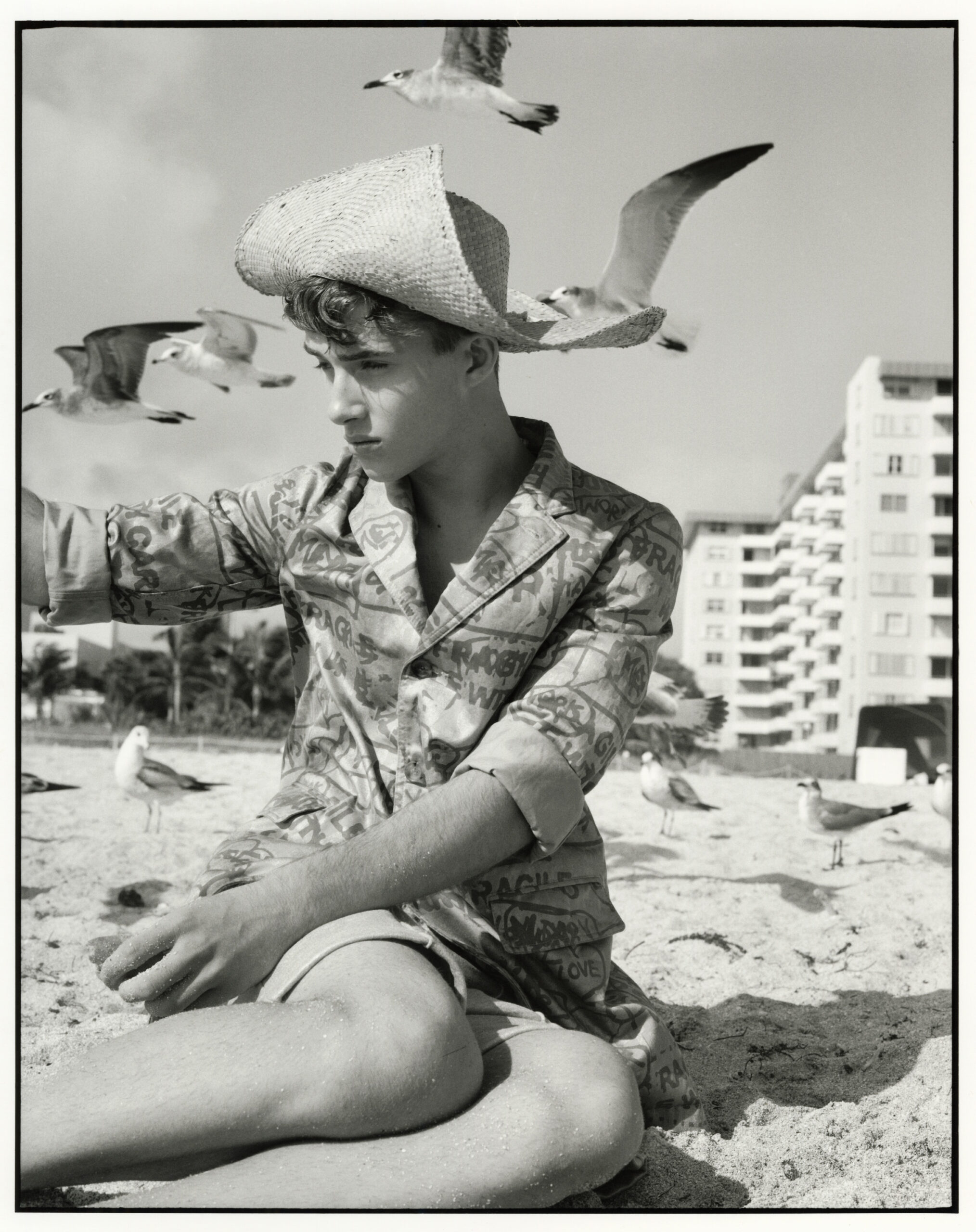

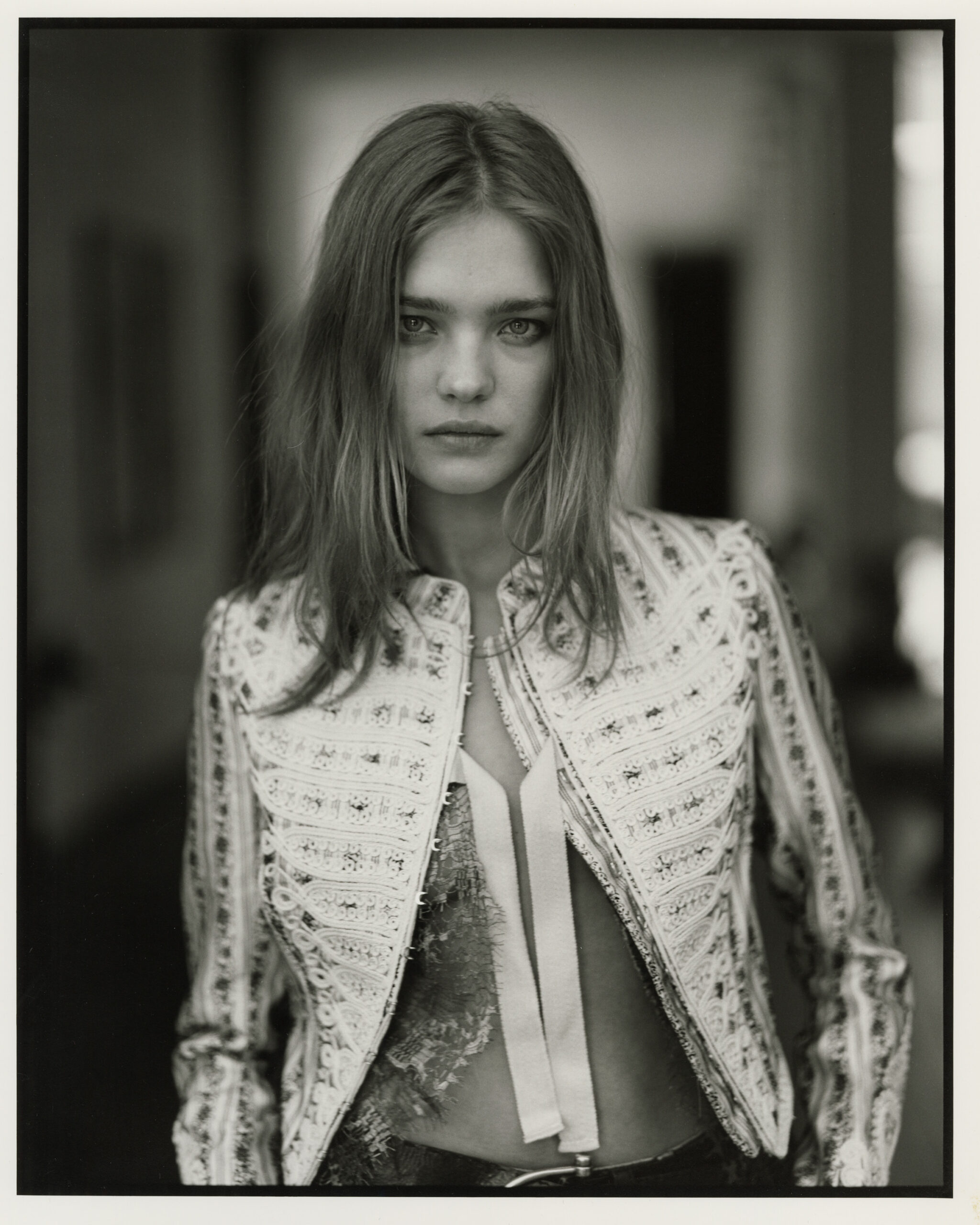

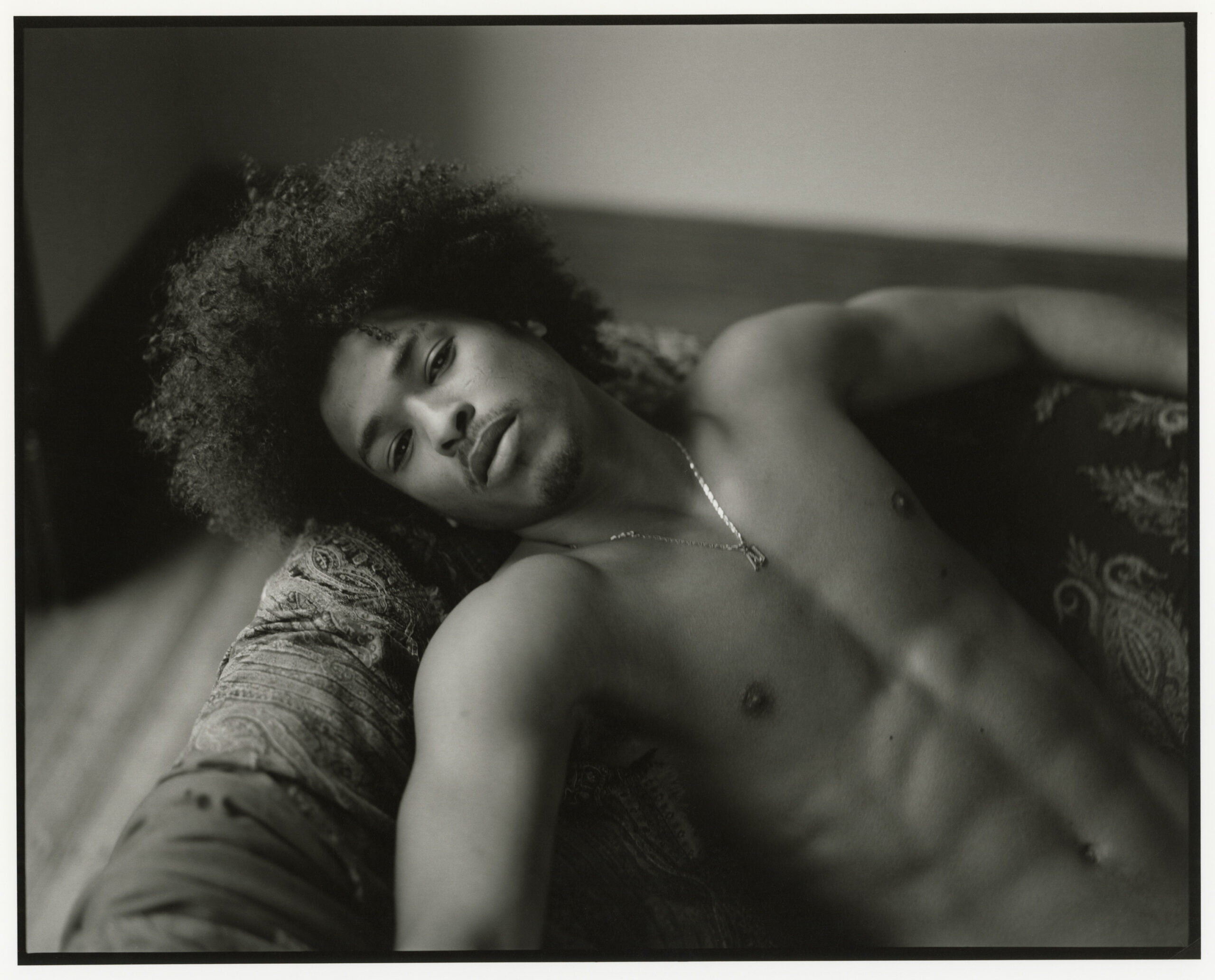

The pioneering work of David Armstrong, the iconic New York-based fashion photographer of the early 2000s, has never been published in print since his passing at the age of 60—until now. The latest issue of MATTE Magazine is a collection of 107 darkroom and inkjet prints hand-picked by co-editors Vince Aletti and Matthew Leifheit, celebrating Armstrong’s undying love of beauty, expressed through his signature black-and-white fashion portraits. Also included in the book are three short conversations with Lisa Love, co-executor of his estate; Marie-Amélie Sauvé, his first fashion stylist; and Ethan James Green, his model, assistant, and protégé. Read on for a selection of photographs from the monograph, and all three interviews, published here in full.

———

HOLLYWOOD, FEBRUARY 2ND, 2024

LISA LOVE: I met David by the cigarette machine, at the Museum School in Boston. And we fell in love with each other. He was enchanting. We were both in the painting department which is where he started. I stayed in painting, and he gravitated to photography which is where Nan was. I thought it was the most exciting place in all of Boston. We would just go down to the photography department and stay all night. Most of us had day jobs. Night was when they were printing. It was such an exciting time in photography. My boyfriend went to MIT then and David and Nan just had this whole other life, a really subterranean life as opposed to mine, which was a little stuffier, a bit more European. David and I were attracted to each other. Friendship, love, whatever you call it.

MATTE: What was he like then?

LOVE: David just saw the beauty in everything. He was beguiling and opened a world to me I would never have known. And he was extraordinarily beautiful. I think a lot of times you look at David’s work and even though it’s in these incredibly kind of precarious and terrifying situations, somehow there’s this sense of utter beauty in whoever the person is that he’s photographing. Like him, beautiful and precarious. And he had this insane intellect and romanticism and a sharp wit, he loved to read historical novels and poetry. His brilliance and intelligence were never pompous or overpowering. He was mesmerizing. There are very few people in the world like him.

MATTE: How did you get into fashion? Since you are now an editor at Vogue, did you and David work together in that capacity?

LOVE: By accident. Arthur [Elgort] came to Boston to do a story about an arts student moving to New York, I wore a burberry coat and carried a portfolio. After graduating we all flocked to New York. I got a huge painting loft, and David and all of them were moving to New York. They got a place on Avenue A. And so we were all in New York together. But four months later I was sent to Europe to do something for Chanel. I never came back. I stayed in Paris. I thought, oh, I’ll just model to support my painting. I moved to Paris and I didn’t see David for years. I also didn’t see a paint brush again. His fashion thing had nothing to do with me. That was James’ fault.

MATTE: Oh really?

LOVE: In fact, when he started doing fashion, I wrote to him and I said, “I thought you would be the last one to sell out.” By then I had left Paris for Los Angeles.

MATTE: How did he react to that?

LOVE: He laughed. He loved beautiful things. It made sense. Actually I hadn’t even seen a lot of his fashion pictures until now, and when you look at the pictures in the magazine, they don’t look like fashion. They just look like David’s pictures.

MATTE: The pictures are so beautiful and only he could have made them. When did that period come to an end?

LOVE: David died here in LA in 2014. But I wasn’t here when he died, I was in Oaxaca at Catherine Opie’s wedding. I also wasn’t there during the fashion years. I was far away watching him and it was exciting that he was embraced by such amazing designers. And for the first time he had money! His work didn’t seem compromised in his fashion pictures.

MATTE: What was his service like?

LOVE: The summer before he died he came out here to do a series of pictures. He stayed on Wilton and Melrose and overlooked Hollywood Forever Cemetery. He chose to have his service there. Rudolf Valentino and Jayne Mansfield were buried there, he said. It was on the day of the dead because he died in October. And the entire cemetery was full of oversized skeletons and marigolds. He would have loved it. Maybe he planned it that way.

MATTE: Were you looking at fashion magazines with David and Nan during those earlier years? I understand they were looking at magazines that they would shoplift together when they lived with the queens in Boston, and that they were looking not only at fashion photography of that time (the 1970s) but also earlier photographers of the 30s and 40s like Louise Dahl-Wolfe.

LOVE: I can’t say I did. He and Nan did a lot of dressing up. I grew up in fashion so it wasn’t as exciting for me as them. They were going out at night and they were spectacular and dressed up. I would go with them, and wore a Howard Johnson’s uniform. I was probably just the sober driver. But I felt like I was rolling with the cool kids. I had a car and they didn’t have cars. It was a bit scary because they were in bad places. They had their cameras held together with duct tape and pockets full of film.

Nan’s career clearly eclipsed his. But I don’t know if he noticed it. He didn’t care so much about that. Together they spoke their own language. And, so I think fashion was a really great way for him to get out of her shadow. And away from all this hard stuff and focus on the beauty and the light that he saw in things. I also think it was a good place for him to rediscover what he saw in pictures and why he took pictures in the first place. Whatever he took photos of—even an addict falling off the table—there was a sense of real beauty in it.

MATTE: When I’ve talked to Steven Koch who is the steward of Peter Hujar’s estate, he seemed to be kind of a stable force in Peter’s life. Peter was mostly friends with these really bohemian people, but Stephen who inherited his work was a professor, married to a doctor. Do you think that’s why David trusted you to know what to do with his work after he died?

LOVE: Everybody needs that person. The sober driver. Yes.

———

PARIS, MARCH 25, 2024

MARIE-AMÉLIE SAUVÉ: I met David through a mutual friend. I thought his work was really beautiful, artistic and sensitive. The first fashion story I did with him was with Emma Balfour who had, at that time, retired from modeling. I don’t know how old she was then, but she’s still modeling now, actually. But yeah, we did that story for French Vogue, shot in an apartment in Paris. I was happy to work with him because, for me, it was really different compared to working with other fashion photographers.

MATTE: How was he different?

SAUVÉ: Because the pictures were quite simple, in a way. It was a lot about the light: how he positioned the model in the light, with great sensitivity. It was more about her, about the character of the girl he was photographing. The person herself. Of course, the fashion was there, but the way he was taking the picture was more about her, in a very intimate way, with no artifice. It was really a modern way to make fashion photography. And it was a bit grungy and cool. I liked it a lot, the fact that there wasn’t too much hair and makeup, just beautiful lighting and a simple setup, yet artistic at the same time. His were very, I would say, feminine and sensitive pictures.

MATTE: So it was more about the personalities of the models than about the clothes themselves.

SAUVÉ: Yeah. I wanted to work with him because it was another way to approach fashion photography. So that was interesting. He’s an artist, so it was more of an artistic approach to fashion photography.

MATTE: Who are the other photographers who you’ve worked with the most, just out of curiosity?

SAUVÉ: I’ve worked with so many photographers. At the beginning of my career, I worked with Guy Bourdin, Helmut Newton, Norman Parkinson, all the old photographers when I was assisting. And after I worked with David Sims, Craig McDean, Steven Meisel… so many photographers.

MATTE: Everyone.

SAUVÉ: Yes, everyone.

MATTE: But it sounds like even having worked with all of those people you were interested in working with David for his own sensibility?

SAUVÉ: Yeah, of course. Because he was bringing something to fashion, in a way. His approach was fresh because I don’t think he was so obsessed with fashion. He was obsessed with the person he was photographing, trying to understand the person he had in front of him, but not so much with fashion. That was really refreshing. I remember Bourdin was more about the composition and the models than fashion, and the way he photographed fashion was to twist it to fit his very specific, artistic eye. And in a different way, I think David Armstrong was like that. Of course, the photography is absolutely not the same. The thing with David Armstrong was that there was no artifice. You know what I mean?

MATTE: Yes.

SAUVÉ: Usually, there was not a lot of preparation except for saying, “Okay, we’re going to photograph this model in that place, in that location,” and that was it. It was up to me to prep the fashion in a way where the fashion had to be strong, because his vision was very simple, in a sense. If I wanted the fashion to stand out, I would have to prepare the looks beforehand and try to create strong looks.

MATTE: One of the things that we have been thinking is that he was really able to adapt fashion to his sensibility and that it wasn’t compromising his work or selling out.

SAUVÉ: Never. Never. He was never compromising in his work. Absolutely not. And it is why he was pure. He was so interesting, because of that. He was really bringing his style and his sensibility to fashion photography.

MATTE: So that shoot for French Vogue was the first time that he did a fashion picture?

SAUVÉ: I don’t know exactly, but I think it was probably, yes, one of the first times he was photographing fashion.

MATTE: What was he like on set? How was he talking to the models?

SAUVÉ: I think he was looking to see a kind of spirit in the model. I don’t think it was about directing them. We chose the location, the light, everything. And then he let the model be herself, rather than directing her. It is why the pictures were so pure and so beautiful and so true. It was not at all artificial. It was the opposite of artifice.

———

MANHATTAN, MARCH 25, 2024

ETHAN JAMES GREEN: David shot me for his book 615 Jefferson Avenue in 2009. I was 19 years old, and I’d been living in the city for about six months. When I met David I told him that I was modeling because I wanted to be a photographer instead of going to college. He seemed excited by that, and right away, he said, “you should shoot in my house sometime.” David’s place was beautifully lit, a perfect setting for portraits, so for someone who had only a camera, this was a huge opportunity. But it took me a while to take him up on his offer. I was intimidated by the photo shoots I’d been on up to that point.

MATTE: Where are you from?

GREEN: Michigan. But I started modeling in New York when I was 17.

MATTE: Did that happen through the internet? How did you eventually become so close with David?

GREEN: Yeah. I feel like I was a part of the first wave of self-discovered internet models. I was embarrassed that I approached agencies with portraits shot by myself and my friends, rather than being discovered in a mall like so many models. When I moved to New York I felt out of place, but David made me feel much more comfortable with myself. I grew up in an environment like Jesus Camp [the movie]. I had so much hate towards gay men. I felt scared of them. I didn’t want to be gay, but when I met David, all of a sudden there was a gay person in my life that I actually aspired to be like. Living in New York as a young person, I eventually hit rock bottom from going out and doing too many drugs. What got me through was a renewed desire to start taking pictures again. I finally asked David to shoot in his house, and when he saw me reviewing the first images from the day, he said, “Ethan doll, that’s fucking divine.” He breathed confidence into me throughout the rest of the day. At the end of the shoot, the team left and it was just me and David. I mustered the courage to ask to work for him, and he said, “I’ve been waiting for you to ask.”

A lot of the work was just cleaning his house, but he helped me stay in the city because I wasn’t making a lot of money as a model at that age. So I cleaned David’s house and got to know him more while assisting him on set. I would open the V-flat or hold a reflector or pick up half-drunk glasses of Coke and Bloody Marys. It was amazing just to see him work, because he was so open, and he wasn’t threatened by anyone. At times, he would encourage me to pick up the other camera while he was shooting for magazines and be like, “Shoot behind my back. My friends and I used to do that. If you find better light, let me know.” I don’t know any other photographers that would let their assistants do that.

Half the time I went to his house, we’d just sit and smoke while he would review my latest pictures on my iPad. He would hold his cigarette in his fingers or his mouth, and I’d watch it slowly turn to one long ash. He would only inhale every so often, mostly holding it in his mouth as it disintegrated. I think back to these moments with him, which are some of the most vivid memories from my first years in New York. Our relationship was cut short because he passed away when I was 24. I wish I could go see him at that brownstone now. I was so lucky to have him in my life. I don’t know where I would be if I didn’t meet David. It’s almost scary to think about sometimes.

MATTE: Most photographers, when you’re assisting them, don’t really want to know about your personal work. And I also think there’s something where many models have a photography hobby, and I’ve seen photographers who are dismissive when models talk about their own practice. So, I think for David to recognize that you were serious about it and then really invest in you as an artist is unique. Were there other people that he fostered in this way?

GREEN: David had close relationships with a handful of people, like Boyd and Jared, who modeled for him regularly. David opened his home to a lot of people in his creative community. I know Jared lived with David for years, and he took on an almost parental role after a loss in Jared’s family. Being an aspiring photographer, I felt we had our own connection through shooting together. He told me how much I reminded him of a younger version of himself. I so badly wanted to be like him, so hearing that was huge.

MATTE: As a model, was he different to work with than other photographers?

GREEN: Every time David shot me, I was in his house or backyard. I assisted him on a few shoots elsewhere, but he almost always chose to shoot in his house, which set him apart from other photographers. When you worked with him, you’d enter this space he’d created, somewhere separate from the outside world. His calmness disarmed you and welcomed you in. Models came to 615 Jefferson from all over, but David found a way to connect with all of them. It takes a special kind of person to do that. His approach to fashion felt so different from other photographers. It’s impossible to recreate since so much of his work was the result of how he interacted with his subjects. His fashion images are aging so beautifully; a lot of them are almost painterly. He was truly ahead of his time.

MATTE: I think you’re right about the world not being quite ready for his fashion work, at least in the mainstream. I think particularly, there’s a kind of gender play that he predicted I think, or maybe partly created. It was like he was able to make fashion suit his sensibility and his way of seeing.

GREEN: Looking at David and his friends when they were younger reveals the blueprint for so many people in the city now. They’re a clear reference point. His work would be much more in demand now, but at the time it was overlooked commercially. He did a lot of iconic editorial stories for a range of magazines, but the consistent money jobs were catalogs for Anthropology or InStyle Magazine, because they always had big budgets. He also liked working with them because his mom read InStyle, so his work would reach her.

Integrity was huge for David, though. If a job wasn’t suited to him, he wouldn’t do it or he’d have a lot to say about it. He would reply with a funny, perfectly bitchy email. He became notorious for those. But his bitchiness was because of his integrity as an artist. If the job wasn’t him, he wasn’t going to do it. This inspired me when I started getting jobs as a photographer.

MATTE: What do you think you have taken from him?

GREEN: Before I met David, I wanted to be a fashion photographer. As I got to know him, I began to see the scope of photography and how rich photos can be outside of a fashion context, when clothes don’t overshadow everything. It’s funny I say this because I do so much fashion work, but he helped me realize that fashion isn’t the end-all and be-all. David also taught me how to communicate with people on set: making sure people feel at ease when you’re working, talking with your subjects, lying on the ground, rolling around. He taught me that natural light is the best light; it’s the most timeless and the most beautiful. See, I can’t even sum it all up, all the things I learned from him. Maybe the most important thing was just seeing how to hold yourself in a setting like that, how to be the photographer, which is huge. When I’m on set, I always remember his advice: “if something’s not working, try the opposite.”

MATTE: Do you share anything about a sense of beauty?

GREEN: In my personal work, my group of subjects reminds me of David’s. So much of my work is about celebrating beauty without trying to change it. So yeah, I think beauty is important to us both. I also collect beautiful things. I love having my antiques and my art collection. Like David, I love finding beauty in people and things.