NYFF

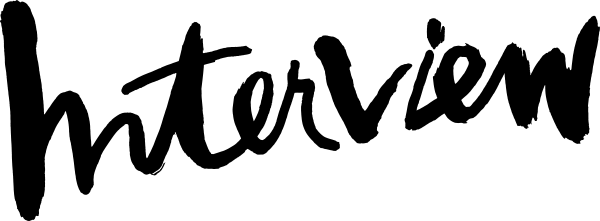

RaMell Ross Wanted to Play in the NBA. Now He’s Opening New York Film Festival.

WEDNESDAY 1:58 PM OCTOBER 2, 2024 PARK LANE HOTEL

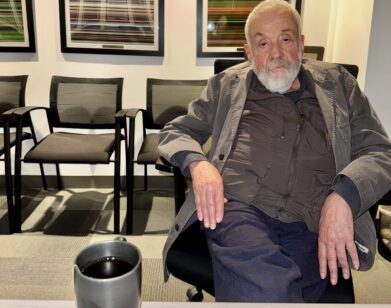

There are hundreds of filmmakers showing their work at this week’s New York Film Festival, but it’s safe to say only one played Division I NCAA basketball. That would be RaMell Ross, director of Nickel Boys, who at one point was nominated as a McDonald’s All-American hooper and harbored real ambitions of one day playing in the NBA. Eventually, he discovered his love of art, courtesy of a college course on William Faulkner, and now he’s premiering his debut narrative feature, an adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s novel of the same name that feels like “a video game that you and Arthur Jafa made together,” as Jeremy O. Harris put it. After the film’s premiere, he found Ross in the lobby of The Park Lane Hotel to talk astrology, art school, and hoop dreams.

———

JEREMY O. HARRIS: How’s it going here at the Park Lane Hotel?

RAMELL ROSS: I must say, I feel like royalty in a bizarre way. I can’t believe I have all this food and an all-ceiling shower and a Central Park view.

HARRIS: Did they give you a bathtub?

ROSS: There’s no bathtub, but it feels like there could be.

HARRIS: If it doesn’t have a bathtub, it’s not giving luxury to me, especially as a tall man.

ROSS: How tall are you?

HARRIS: I’m 6’5.

ROSS: I’m 6’6.

HARRIS: You play basketball, right? Did you know Yorgos Lanthimos also played basketball?

ROSS: Wait. I don’t mean to put his resume on blast, but like, to what extent?

HARRIS: I feel like he was on the Greek national team.

ROSS: Fuck. I’ve gotta talk to this dude. I mean, I’m always hesitant to talk to other filmmakers just because like, what do we really have in common? But like, basketball is me. I am basketball.

HARRIS: But how basketball are you?

ROSS: I mean, I forcibly moved myself away from constantly thinking about it as I realized that I wasn’t going to the League. But for a good 8 years, it consumed me in the same way that art does.

HARRIS: How close were you to being in the NBA?

ROSS: I mean, I was nominated McDonald’s All-American, top 100 basketball players in the US. I played professionally for one year in Ireland. I mean, you know, everyone says this, but I was supposed to go to the League! Like, my boys were in the League!

HARRIS: Wow. Did you play with anyone that we like, now know really well?

ROSS: I mean, I’ve played with [Michael] Jordan. Jeff Green was on my team and he went to the League. Ruben Boumtje Boumtje went to the League. I mean, I still dream of the thing, you know?

HARRIS: That’s wild. Are you gonna make a basketball movie next?

ROSS: I thought about it, but I just don’t know how.

HARRIS: Are there good basketball movies?

ROSS: He Got Game. You’ve seen?

HARRIS: Of course. I’m curious about how consumed by art you were when you were in basketball.

ROSS: Not at all.

HARRIS: So you fell into art?

ROSS: I realized my interest in basketball was artistic-leaning.

HARRIS: There’s a really great anime about basketball, Kuroko no Basket.

ROSS: I’ve never seen it.

HARRIS: It’s great, but it’s basically about this kid who’s from a basketball town. The middle school basketball team had the five best players in the world, but no one knew that, secretly, he was like the sixth best.

ROSS: I’m going to take a picture of this, because I want to watch it.

HARRIS: I promise you, it’s my favorite thing. Everyone has a special power. Like, one’s really good at dunking, one’s really good at three-pointers.

ROSS: Like, the Power Rangers of basketball?

HARRIS: Yes, but his secret power is that he’s really good at passing. And you’re trying to see if Kuroko can make it all the way with his brand of basketball.

ROSS: With his facilitation abilities.

HARRIS: Yes, yes, yes. He’s great.

ROSS: Did you play sports?

HARRIS: No.

ROSS: Do you get asked that all the time?

HARRIS: I hate basketball because of this.

ROSS: That’s why I hate rap. Everyone’s like, “Do you rap?” I’m like, “Fuck you. Just because I’m Black?”

HARRIS: Wow.

ROSS: No, I’m just joking.

HARRIS: I mean, you could hate rap. I started to resent basketball because I wasn’t very good at it and I kept being forced to do it. I really liked dance and gymnastics but because it was faggy, I couldn’t really do it. Even the high school I went to, I was the first Black person that went there that wasn’t on a basketball scholarship.

ROSS: Woah. So everyone was confused.

HARRIS: What’s your sign?

ROSS: I’m a Taurus. Does that make sense?

HARRIS: Well, I don’t know yet. I mean, you like luxury. That’s a Taurus trait. What thread-count are your sheets at home?

ROSS: I have no idea. All my sheets are from Walmart. I shop at all thrift stores. I don’t buy things new.

HARRIS: That’s not very Taurus at all. The reason I asked for your sign was because it’s a very vulnerable thing to go from being the tall sports guy who played basketball at Georgetown to being like, “I’m gonna go RISD.”

ROSS: In that same lane, when I knew I wasn’t going to the League anymore, it was devastating, and I started to actually read and become interested in literature and poetry and writing while still playing basketball. There is an actual chasm where the artist in me is present, but the culture is not accepting of that. So I’m just a weird guy on the Georgetown basketball team, you know? Everyone was like, “That guy is weird.”

HARRIS: What class was it that changed the game?

ROSS: I love your questions.

HARRIS: Is this your best interview ever?

ROSS: I mean, I told other people they’ve done well. But this one, it seems like you’re interested in me in a way that no one else has been, which I really appreciate. Anyway, it was a class called “The Fiction of Faulkner.”

HARRIS: Faulkner, my absolute favorite.

ROSS: Professor Wayne Knoll. And the way that he talked about Faulkner, it was un-fucking-believable. What’s it mean to be outside of time? Like, what the fuck are you talking about? First of all, I had to look up every single word in the book. And it wasn’t even that complex, I just didn’t have that vocabulary, you know? It was kind of incredible. Then I found photography when my mom died, which was my fifth year at school, so I’m starting to become an artist and actually seeing myself as one. And that year, I’m like the sixth man on the team and I scored nine points against the number one team in the country. I know I’m not going to the League but like, there was finally something fulfilling about all those years of work. And then my mom gets sick and dies really fast and I just kind of lose my mind a bit, you know? I start fucking up on the basketball floor, I start not caring. Then I take an art class, and I wasn’t quite hooked on it as a career, but I was hooked on it as a meaning-making thing. They’re showing Diane Arbus, they’re showing William Eggleston. I’m like, double-exposing squirrels and birds. That was the best.

HARRIS: It’s beautiful that there was this metamorphosis from tragedy into beauty. How do you go from photography at RISD to making Hale County This Morning, This Evening, which is one of my favorite movies.

ROSS: Thank you. Once I learned how to make an image “beautiful” or whatever, that became shallow, so I began to only care about meaning and important things, or whatever that means. So I was in Alabama before I went to RISD.

HARRIS: You found your subject, basically.

ROSS: I found my character.

HARRIS: Did you like your time at RISD?

ROSS: Honestly, it was great because I got a lot of attention and I found my voice in Hale County and went to grad school so that I could continue doing it. Most of the people that came in went to grad school to find their voice, so I was just way ahead of them.

HARRIS: The other thing I was going to ask you was how often you play video games.

ROSS: None.

HARRIS: You don’t play any video games? Is it offensive that I felt parts of Nickel Boys felt like a really exciting video game? Like, a video game that you and Arthur Jafa made together, or something. There’s a playfulness to your camera.

ROSS: I mean, I love that line. That sounds fucking cool.

HARRIS: What’s the question you’re most tired of being asked?

ROSS: I think, in general, I’m most annoyed at people calling the camera a gimmick.

HARRIS: They called it a gimmick?

ROSS: Yeah. Like, the gimmick collapses on itself. Weird stuff like that.

HARRIS: So you’re reading the nasty reviews?

ROSS: I think I’m gonna read every single one. Iif I don’t have critique, I don’t know what the fuck’s going on. And it doesn’t mean I don’t have a voice and do my thing, but I want to know what people think. And hopefully, I can incorporate it so I can communicate better. Like, I’m not trying to work in a fucking bubble.

HARRIS: I get that. I’m self-punishing, so I read them all, but

ROSS: I think I’m also self-punishing, but I wouldn’t have led with that.

HARRIS: Well, I think you made a very, very beautiful film. It’s kind of a magic trick of a film, too. In many ways, it’s a new language for a type of viewer, the way in which your story is patient, the way in which your story is shot. It’s really special.

ROSS: Thank you, Jeremy.