ICON

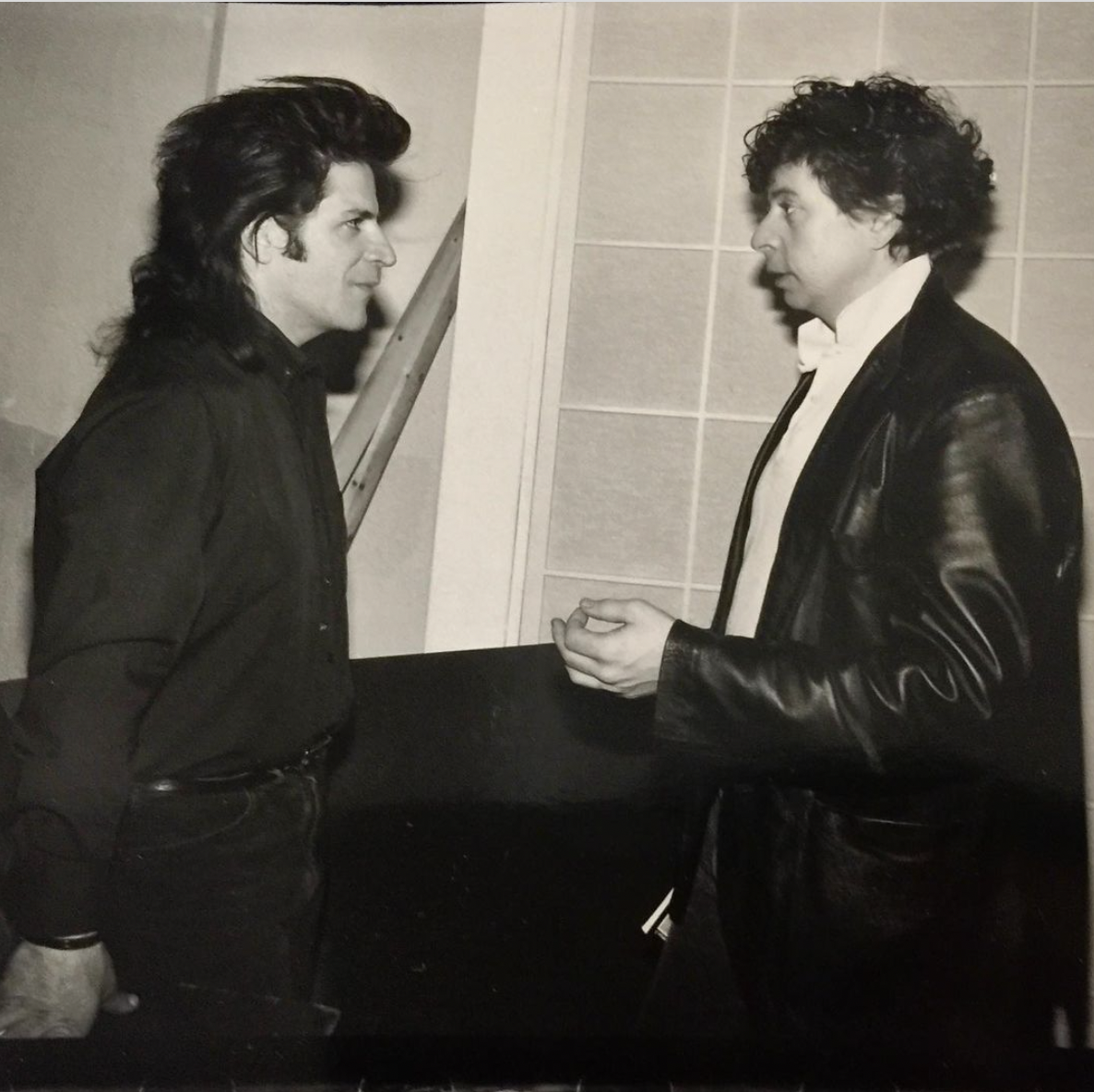

“How Do You Feel About Getting Old?”: Robert Longo, in Conversation With Richard Price

In his new two-part exhibition, artist Robert Longo is going back to where it all began. On view at Pace and Thaddaeus Ropac concurrently is Searchers, a series of drawings including new works revisiting his Combine formats of the 1980s and the montaged image sequences that brought him notoriety in the late 70s, before a quick and ill-fated brush with Hollywood. “Johnny Mnemonic was a fucking horrible experience,” remarked the celebrated artist, talking about his ’95 sci-fi feature to his long-time friend and fellow filmmaker Richard Price. “I was lost for a while, so I went back to where I started from, which was ripping pictures out of newspapers.” Longo’s two shows include his hyperrealistic charcoal drawings, many of which draw from politically-minded imagery that communicate what the artist otherwise struggles to verbalize. On a call with Price, who appeared in Longo’s 1987 short Arena Brains, Longo confessed to feeling nervous for the first time as he prepared to debut his new works. “I always say terror keeps you slender,” Prince reassured him, and the two soon got to talking frankly about burnout, filmmaking blunders, and the pleasures and pitfalls of getting older.

———

ROBERT LONGO: You have a new book coming out and I have a bunch of big shows happening. We’re evolving. I think what I’m doing now is the best work I’ve ever done and I think your book is incredible. How do you feel about getting old, brother?

RICHARD PRICE: I hate it. I’m not old, but I hate it anyhow. Listen, I got my Geritol, I have my truss. It’s on my mind. It’s like my body’s telling me something. Nothing serious, but I say “ouch” a lot more often.

LONGO: When we were younger, we thought we were indestructible. Now we see the light at the end of the tunnel, and I’m running the other way. Every time I go to the gym, it’s like, “Fuck, I hate this, but I gotta do it.”

PRICE: Gotta do it.

LONGO: All of a sudden, I’m being dragged into a future that I don’t want to go into. But we as artists are leaving behind things that are how we want to be remembered, like the books and the artwork.

PRICE: Legacy is important. What we do lives beyond us. So when I die in 40 years at the ripe age of 150, maybe people won’t even be reading books or looking at art. I wanted to ask, if you went back to the early ’80s when people were going to an exhibit of Men in the Cities and all of a sudden, you got swooped into this year, how would you relate to 1981 Longo? Would you recognize your work?

LONGO: I still think everything is powered by the same rage and passion. I think I’m smarter, more worldly. Back then, I was incredibly aggressive about what I was trying to do, but I still am. Making art has so much to do with wanting to share how you see the world. And what’s interesting is how the work has expanded its focus, but there’s a consistency with Men in the Cities and what I do now because I try to make work that happens every time you look at it. I think that’s really important. I don’t know if you ever do this, but I’ve gone backwards to go forwards.

PRICE: Can you explain that a little?

LONGO: Yeah. After I made Johnny Mnemonic, I was one of the artists that was blamed for the ’80s. Johnny Mnemonic was a fucking horrible experience with dealing with Hollywood people, so I was lost for a while. I went back to where I started from, which was ripping pictures out of newspapers. I decided to make a drawing a day, and I made this series called Magellan, which was 366 drawings. That became the linchpin of everything I’ve done since then. Now, I have these two big museum shows, one in Vienna, one in Milwaukee, and the show in London is all this new work. It’s the first time I’ve been really nervous about doing an exhibition. I keep on thinking about all the things that can get fucked up and go wrong, so I’m excited about that.

Untitled (Pilgrim), 2024. Mixed Media, 5 parts. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul ©. Photo: Eva Herzog.

PRICE: Fucked up and go wrong is very exciting. I always say terror keeps you slender. Tell me about the first two shows that you mentioned, the museum shows.

LONGO: Literally, in one week, I went from Vienna, the home of Freud, to Milwaukee, which is the home of the—

PRICE: The home of the Milwaukee Braves who beat the Yankees in 1957 in the World Series. Nothing else.

LONGO: Milwaukee is actually a really beautiful place. It’s such an American city, which is great for me because I feel like such an American artist. I think you are a really American writer and it’s a bit of a curse for both of us. But the show in Vienna is a retrospective that goes back to 1981, so Men in the Cities are in it, Guns are in it. It’s a pretty huge show. The show in Milwaukee is also pretty big, but it’s work from the last decade and it’s the most intensely politically charged work I’ve made. I think it’s going to be really interesting because it’s going to be up during the election.

PRICE: I remember at one point, you had criticism because you weren’t engaging in what’s going on in the world and you got so pissed off because everything you do is so on point to what’s going on in the world. And if they didn’t see that, they weren’t born yet. Especially this work, I think that’s some of your best stuff I’ve seen. When they look at the Trumpian imagery, the reactions of riots, it’s more frightening than if I saw just a photograph.

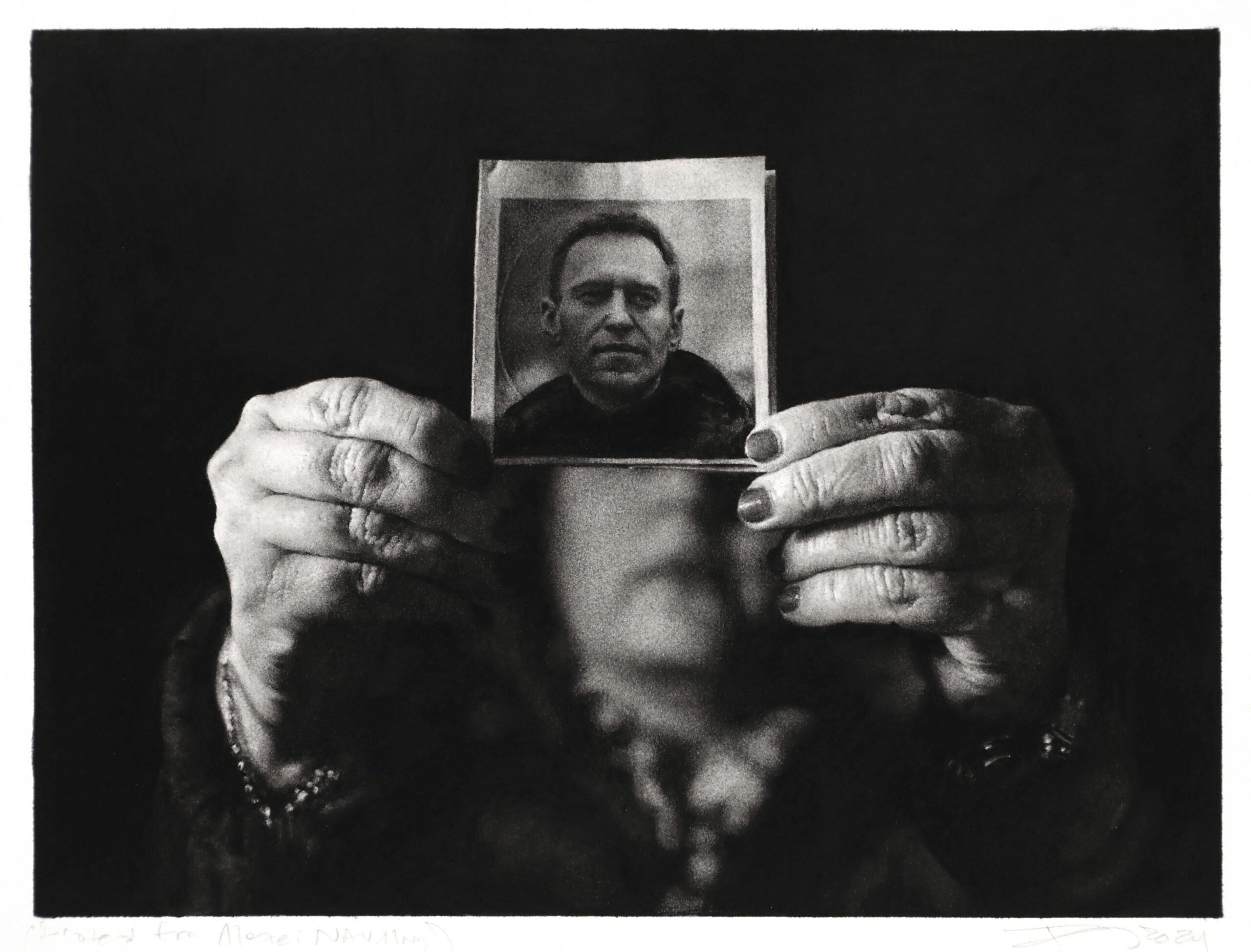

LONGO: That’s good, because the title of the show is The Acceleration of History, and it’s basically a group of work that I call the Destroyer Cycle, which is motivated by work that was made while Trump was in office. I try to buy the images as often as I can, and then I cut them up and piece them together to make this image that somehow evokes ancient archetypes. I’m trying to make an image that is more than just a click of a camera. So what you’re seeing is not simply a copy of a photograph from the newspapers. It’s a highly constructed, composed image that is trying to be more than what you’re looking at. In that sense, it becomes important that there’s a familiarity to it, but at the same time, I want to transcend that. I think about that in relation to your books. I don’t understand how you wrote this book. How do you keep track of shit? How do you weave all this stuff together? The level of detail that comes out every time I’m reading your book, and how you construct pictures.

PRICE: First of all, I make 7000 lists, and every one of them winds up in a paper shredder.

LONGO: Are you still writing on yellow legal tabs?

PRICE: No, I’ve moved to a manual typewriter. [Laughs] No, I’m using an iPad. Like anybody else over the last 20 years, I don’t have any handwriting that’s legible anymore. My handwriting is like I held a pen with my teeth. But to the question I asked you about whether you would recognize your work, the older you get, the more nuance you have to your eye and your images. You respect the small things more. It’s the bits of life. I feel like I have an ability to interpret what I see and pick out what’s important and what’s not. Nothing feels gratuitous to me anymore in what I do. Since the ‘80s, we’ve been through so many changes and some were painful and some were amazing. But my love is always the urban landscape. My love is small talk. I tend to put in cops and crimes in there because if you have a crime, it helps you organize a panoramic.

Untitled (Mahsa Amini), 2024. Graphite on paper. Image 17.1 x 20.3 cm (6.73 x 7.99 in). Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London · Paris · Salzburg · Seoul

LONGO: Okay.

PRICE: When I did Lush Life, it was about the Lower East Side and there were seven planets there. There were the Bohos, there were the Orthodox Jews, there were the housing project people, there were the Fuzhan Chinese. It’s a solar system. So how do you write a story about a solar system? I discovered that a crime is very orderly. The investigation brings in all these disparate people as witnesses, as victims, as perpetrators, as indifferent. They have nothing to say, but yet it’s a horse to ride through a very complex landscape.

LONGO: Clockers was your first voyage into cop world. I remember you coming back one day to my studio with your two little daughters. They were on the floor crawling around your feet. Meanwhile, you’re telling me this horrific story about a crime scene where some kid had been shot with an Uzi. And you’re describing this scene so vividly. Clockers was the first thing with cops, right?

PRICE: Actually, it was Sea of Lovers, the Al Pacino movie. But I’ve never talked to a cop before that. There’s that old creative writing cliche, write about what you know. Well, maybe you don’t know shit, maybe you’re in your 20s, all you know is your dick, and you can only write about your dick so much. So you keep expanding what you know by reaching out to people and it’s infinite. It’s like trying to drain the ocean with a colander, infinite experience. The heart of my work is going out there and hanging out, learning things. I love that so much more than actually writing. And when COVID happened, I couldn’t do that. So with this book I have now, Lazarus Man, it’s not like I went out and talked to anybody. It’s about, “Holy shit, I have this reservoir of experience now.” Jane Austen never left the cottage. Robert Louis Stevenson traveled around the world. I’ve been finding different, more subtle ways to make explosive art. And I’m so proud to be your friend. I’m proud to have witnessed this journey, the darkest parts and the brightest parts, because I can relate to it so much.

LONGO: It takes me fucking years to read a book. And we’re both fortunately married to quite extraordinary women. I asked my wife, Sophie, if she would read me this book while I was doing all this work. She read me the book and she loved it. It was interesting to have someone read words out in the air. It was wonderfully more visual than ever. I don’t want to give too much away about the book, but the end of the book could be a self-help pamphlet. How the worst shit in the world can happen to you and it may be really good. I was crying. It was incredible.

PRICE: Yeah, I think the essence is even though your grief is at this point where you can’t breathe, hang on because the worst thing that ever happened to you over time will become the best thing that ever happened to you. That’s a tough sell, but it’s just a blind faith feeling. Every time you encounter unbelievable sadness or pain, you’ve been there before and you’ll be here after this. Pain, grief, tragedy, it’s part of life. Every time it visits you, say, “I’ve been here before and here I still am.”

LONGO: Agreed.

PRICE: You mentioned Sophie and Lorraine, who we’re married to. Who we share with has for me has become a huge part of my growth.

LONGO: This morning I was saying to her that I realized our relationship is like when Legos click together, and other relationships were more like assembling a Kia. My work is aggressive in a way, but I want it to be hopeful. I read someplace, “Hope has two beautiful daughters; their names are Anger and Courage.” I think you and I have a lot of hope.

PRICE: Yeah, I had a lot of anger too.

Untitled (Hunter), 2024. Mixed media – 5 parts: dye sublimation print, plexiglass, 3D color print, video, and charcoal on mounted paper, 88″ × 55″ × 6″. Pace Gallery.

LONGO: I still do.

PRICE: But if it’s a sense of outrage about the world in your work, you take that and you create something so vivid and luminous. It’s like an alarm. Anybody that goes into a gallery, it’s like they’re getting hit in the head with an alarm bell. “This is where we are right now.”

LONGO: There’s a borderline where I get a bit nervous sometimes, though. I see a lot of recreational outrage. I go back to history a lot and look at what’s going on in the world. When the whole thing with Gaza happened, I could not figure out how to deal with it. I’ve had situations where people will see black and white images in newspapers and call me up and say, “It looks like your work.”

PRICE: I think I’ve done that once or twice.

LONGO: But the Gaza stuff, I could not figure out how to mediate. So I went backwards to use these two big drawings. One of them was by [Peter Paul] Rubens, The Massacre of the Innocents. It’s a painting where all these people are killing all these babies because they’re looking for Jesus. But it looks like what the scene was like at the Israeli settlement. The other one I did was [Francisco] Goya’s The Third of May 1808, the execution of these innocent people by Napoleonic forces, and these people almost look like Palestinians standing in this wreckage. As an artist, we have this Cassandra curse. We can see the future, but nobody wants to hear us.

PRICE: I think if you make people work a little bit to get it, it hits them more profoundly when they make the connection.

LONGO: But I also think we live in this culture of impatience and when reading a book, you start to realize that attention is power. You wrote a book that’s almost 500 pages, and at my exhibition in Vienna, there’s almost 50 works. Walking through the show is like walking through a movie. When you finish a book, do you go back and read it?

PRICE: I read parts of it. I can’t read it through because my tendency is to say, “Oh my god, why did I write that sentence? This sucks.” But since Clockers, I’ve been pretty good about what I’ve written. Before Clockers, I felt embarrassed. When I finished writing my first four novels, I was like 32. I went away for eight years. I was burned out, plus the coke habit. I went to do screenplays and in that time, I went back to Clockers, I got married, I had two children, I started making money for the first time. I started feeling valued in my field. It took a while for me to get back on the bicycle, but I was a different person afterwards.

Untitled (Black Peony), 2024. Charcoal on mounted paper. 70″ x 120″ (177.8 cm x 304.8 cm) Pace Gallery.

LONGO: What year was Clockers?

PRICE: ’92.

LONGO: So we’re talking about the same time where we both had that moment that made us who we are now.

PRICE: Yes. I’ve known you since 1981. I love your ass and I value your friendship and it’s a privilege to see you do what you do. God bless you for doing it.

LONGO: Well, you make me read books, which is really a tedious thing for me. But I love being able to do that and to travel this road with you has been really great. We float in and out of each other’s lives sometimes, but you come back and rescue me. I remember you’ve always been there for me and I really appreciate it. We’ve been through a lot. I think the book is going to be a great success. I think we’re really good examples of artists that are able to get better as we get older.

PRICE: Because art is not a job. It’s who you are. There’s no retirement. You stay in that action mode because there’s no concept of done.

LONGO: Absolutely. And I love that I cannot understand how you do what you do. You’re like a superhero to me. It’s like, “How the fuck does he do that?”

PRICE: Well listen, what you do is an absolute mystery to me.